Associated Press

PITTSBURGH — Pennsylvania's Marcellus Shale gas drilling companies are recycling more and more of their briny, chemical-laden wastewater, in most cases complying with a request from state officials to keep the pollutants from being discharged into rivers that supply drinking water.

But experts are wondering if a loophole in disposal regulations is still allowing significant quantities of one of the worrisome compounds— salty bromides— into rivers and streams, or if shale gas drillers were only part of the problem.

The new mystery is this: why hasn't the dramatic progress on the wastewater recycling led to equally clear declines in river bromide levels?

An analysis by The Associated Press of 2011 state data released Friday found that of the 10.1 million barrels of shale wastewater generated in the last half of 2011, about 97 percent was either recycled, sent to deep-injection wells, or sent to a treatment plant that doesn't discharge into waterways.

Some of the new disposal trends are also raising other questions. The amount of Marcellus drilling waste injected deep underground nearly tripled in the last six months of 2011, with much of that going to Ohio. Officials there are examining whether the high-pressure injections contributed to a series of small earthquakes near one waste site.

In the same period of 2010, shale drillers sent about 2.8 million barrels of waste —or 118 million gallons— to numerous treatment plants that discharge into rivers and streams.

Those discharges raised alarms when the plants reported soaring levels of bromides in rivers that year. Though not considered a pollutant by themselves, the bromides combine with the chlorine used in water treatment to produce trihalomethanes, which can cause cancer if ingested over a long period of time.

Part of the answer to the mystery may be that the highly publicized plan for voluntary compliance by Marcellus drillers had a little-noticed loophole: it didn't apply to thousands of other oil and gas wells in the state.

An AP analysis of the new state data found that about 1.86 million barrels — or about 78 million gallons — of drilling wastewater from non-Marcellus wells were still being sent to treatment plants that discharge into rivers in the second half of 2011.

"They ought to get all of that out of the water. It's obviously hazardous, it presents a public health hazard. What's good for the Marcellus wells should be applied to the other wells, too," said Jan Jarrett, president of the environmental group PennFuture.

Michael Krancer, head of the Pennsylvania DEP, declined requests for an interview. Agency spokesman Kevin Sunday said in a statement that "other industrial wastewater also has the potential for high concentrations of total dissolved solids," but that existing state standards protect waterways.

After being promoted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's concerns, Pennsylvania sought a voluntary moratorium last May, asking Marcellus Shale drillers to cease bringing the drilling waste to plants that discharge into rivers.

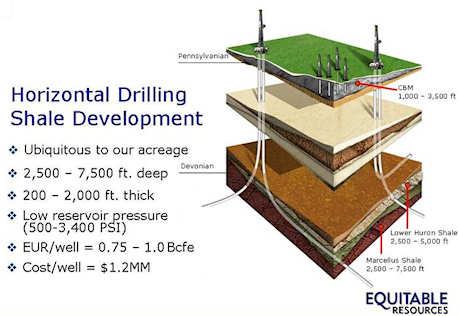

The Marcellus Shale is a gas-rich rock formation thousands of feet underground in large parts of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and West Virginia. Over the last five years, advances in drilling technology made the shale accessible, leading to a boom in production, jobs, and profits — and a drop in natural gas prices for consumers.

Last summer, Advanced Waste Services, a wastewater treatment firm with a plant in New Castle, Pa., noted that a senior DEP official confirmed that the moratorium "does not extend to wastewater from shallow well (aka non Marcellus wells) drilling and fracturing nor does it extend to spent drilling mud and other sludge disposal."

Stanley States, director of water quality at the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, said he believes that municipal sewage treatment plants have stopped taking the brine water, but that other plants continue to do so.

"I think it's still going on," States said of the dumping of fracking wastewater into rivers. "Self-regulation does not work."

Kathryn Klaber, president of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, an industry group, said it was never accurate to blame the shale gas drillers for the whole bromide problem.

"We know there are quite a few other sources going into Pennsylvania waterways," Klaber said. "You have to start looking at other places."

Water quality experts say coal-fired power plants and other industries also produce bromides.

Additional water testing over the last year also appears to have put to rest concerns that radioactivity from the drilling waste could contaminate drinking water.

States said his agency "looked real hard" at the radioactivity issue, but didn't find a problem in western Pennsylvania rivers.

Sunday, the DEP spokesman, said the state's water quality monitoring network shows normal, background levels of radioactivity. "Monitoring at public water supply intakes across the state showed non-detectable levels of radiation; in the two cases that detected any level, the levels were at background," he added.

Pennsylvania also reported recent Marcellus Shale gas production data on Friday. Drillers produced about 607 billion cubic feet of gas from July to December. That's up from about 435 billion cubic feet in the previous six months.

-----

Associated Press reporter David B. Caruso contributed reporting from New York

—Copyright 2012 Associated Press

_1303929693.jpg)

Shell said that if the project goes forward, up to 10,000 people would be working on it during construction. Once the plant is operating, it would employ several hundred full-time employees. Although Shell would not say how much it expects to spend building the plant, it said such plants typically cost “several” billion dollars.

For more information check out Washington Post...